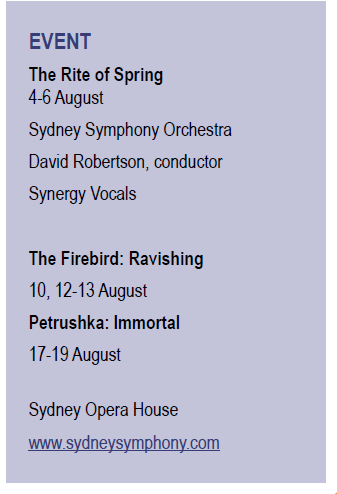

Concerts permit that which the laws of physics do not: bringing together, in the same room, people from disparate times and places. In August, Chief Conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (SSO), David Robertson has selected to perform three Stravinsky ballets, each partnered with an even more contemporary work. The first of the concerts pairs The Rite of Spring with The Desert Music and what interesting men this will bring together.

Concerts permit that which the laws of physics do not: bringing together, in the same room, people from disparate times and places. In August, Chief Conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (SSO), David Robertson has selected to perform three Stravinsky ballets, each partnered with an even more contemporary work. The first of the concerts pairs The Rite of Spring with The Desert Music and what interesting men this will bring together.

With Igor Stravinsky comes Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballet Russes, and Vaslav Nijinsky, original choreographer of The Rite. With Steve Reich, the composer of Desert Music, comes William Carlos Williams on whose poems the work is based. And of course, the tableau is only complete with Robertson himself.

It is interesting to uncover how all these men came to be here. Sergei Diaghilev did with his purse what he could not with the pen (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov told him he had no talent for music). His love of music and the arts made him one of the most notable and influential art patrons of the 20th century. In 1909 he launched the Paris- based Ballet Russes. He had heard, and was impressed by, Stravinsky’s Fireworks and so asked him to arrange some pieces by Chopin for the company. The collaboration was clearly a success as in 1910 he commissioned a full-length score from Stravinsky. This was to become the Firebird. Petrushka followed in 1911 and then the infamous The Rite in 1913.

Like Stravinsky, Vaslav Nijinsky was brought onto the scene by Diaghilev. An exquisitely talented ballet dancer, Nijinsky soon caught Derghiev’s eye. He joined the Ballet Russes and the two became lovers. In 1912, Nijinsky began choreographing for the company and so he was perfectly placed to create the riotous dances for The Rite. The notoriety that followed is the result of all three of these men.

Steve Reich is here at Robertson’s invitation. As he told Fine Music magazine, he feels Stravinsky and Reich share a “use of pulse as the most important human element in music”. At first glance, however, it would appear that Stravinsky and William Carlos Williams have more in common. Born a year apart, they circulated in their own modernist and imagist/cubist circles. Just as Stravinsky and Nijinsky sought to re-invent the worlds of music and dance, so Williams sought to reinvent poetry with his own jutting style. But this is not in fact why he’s here. No, he caught Reich’s eye for a far simpler reason: his name. The symmetry of William Carlos Williams appealed to the young Reich and so he set out to become acquainted with his poetry. The last 10 years of Williams’ life were the first 10 of Reich’s adulthood; the young man absorbed with thirst what the old man had the wisdom to write. In 1983, 20 years after Williams’ death, Reich completed

his composition Desert Music based on fragments of Williams’ poetry. It is fitting that the piece is structured in a similar arch form to Williams’ name: ABCBA.

Last, but not least, is Robertson himself. His great privilege as conductor is to select the pieces his audience will hear. He can introduce them to new works, familiarise them with the lesser known, or bring up nostalgia with old favourites. It is a privilege to be able to ask what motivates his choices.

Sign of the times

Robertson had been a guest conductor of the SSO for a decade before assuming the role of Chief Conductor. In that time, he became known for embracing the avant-garde, performing concerts with multimedia and video projections, and for premiering some notable American works and he has returned the favour stating, “I have performed, I guess, five works of Brett Dean in St Louis… you could say I’m a charter member of the Australian- American friendship society”. Asked how he came to be associated with music of the 20th and 21st century, he answers simply: “I think I’ve always been interested in the music of our time as well as the music of the past”.

This time crossing develops as a theme in his interview with Fine Music magazine. As Stravinsky composed his ballets he pushed further the boundaries of modernity. The tales they are based on, however, are steeped in antiquity. To Robertson, this connection is not paradoxical but logical. As he explains: “In the visual arts at the same time, artists were looking towards the primitive to try to find new ways of expressing visual language. Stravinsky ended up doing the same thing in music so that ‘primitive’ came to be seen as an avant-garde idea.

“So it was to some extent a return to sources in a way that allowed the energy of the original sources to become clear.”

From this perspective, it would seem that Stravinsky was drawing on the trends around him. Indeed, when asked whether he sees Stravinsky as a man of his times and or a timeless artiste, Robertson replies: “I think he was very much a man of his times and worked hard to remain so throughout his life. His collaborations with Sergei Diaghilev turned him into a timeless artiste and that’s a hard thing to live up to when you are in your twenties and you live until your eighties”.

It is easily forgotten that Stravinsky was so young when he changed the face of music. 100 years later it is all just ‘in the past’. Few who were at the premiere would still be alive. Perhaps it is for this reason that Robertson wants to perform three of his ballets (Firebird, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring) in close proximity and alongside more modern works.

Audiences need to be reminded just how much music changed in three years and the lasting influence that Stravinsky had. In Robertson’s words: “These three ballets were the product of an intense relationship with Sergei Diaghilev and his artistic collaborators and they really opened up music in the 20th century in so many directions.

“Having them in close proximity allows one to hear both where Stravinsky was coming from and where Stravinsky’s ballets allowed music to go.”

Music about ‘something’

Where music ‘went’ can be seen in the pieces by Karol Szymanowski and Peter Sculthorpe, performed with Firebird, and Elliot Gyger and Tan Dun, performed with Petrushka. Szymanowski was a contemporary of Stravinsky. His Violin Concerto No. 1 was written in 1916 and is seen as one of the first modern violin concertos, rejecting tonality and romanticism. Sculthorpe composed Sun Music I in 1965. Like Firebird and the Violin Concerto, it very much represents beginnings and the start of something new. It was written for the SSO’s first overseas tour and laid the foundations for original Australian music – it changed history. Gyger has taken the title of his work Acquisition from a movement in The Rite. Dealing with the idea of acquiring the earth, the concert will explore the dark and primitive. Tan Dun’s The Wolf warns humans of their disconnection with the earth. In this work the wolf embodies man, just as a puppet represents him in Petrushka.

All these pieces are music about ‘something’ and, as Robertson explains, “even if you don’t know the specifics of the story, it is clearly music about ‘something’.

“Like listening to a fairy tale in a language you do not understand, the intonation and rhythm of the speaker holds you captivated.”

Reich has a different intention with his work. As mentioned, Robertson connects Desert Music with The Rite because of the elevation of pulse as the most significant human element. It is a minimalist work and Robertson ascribes the marvel in this as being “the ability for small ideas carefully chosen to generate incredible richness in the same way that the four chemicals of DNA can create such a wide variety of life”.

In an interview with Jonathan Cott, Reich said of Desert Music that “if you want to write music that is repetitive in any literal sense, you have to work to keep a lightness and constant ambiguity with regard to where the stresses and where the beginnings and endings are… one has to be in relative stillness to hear things in detail”.

He added that “all meditative practices are based on some sort of silence – inner and outer”. Though there are words, the piece “goes into something completely non-verbal, it leaves language behind”.

Diaghilev, Nijinsky, Williams, Stravinsky and Reich: five men united by their fascination with the primal and the physical. Who knows, if they had met, if they would have gotten along with each other or ended up engaging in fierce debate? In a concert it does not matter, for a conductor tames them to be compatriots. It is through his eyes that they are allies and through his hands that this is realised for an audience. Robertson will perform the Stravinsky ballets because this is music that matters to him. A good performance can convince an audience that it should matter to them, too.

Diaghilev, Nijinsky, Williams, Stravinsky and Reich: five men united by their fascination with the primal and the physical. Who knows, if they had met, if they would have gotten along with each other or ended up engaging in fierce debate? In a concert it does not matter, for a conductor tames them to be compatriots. It is through his eyes that they are allies and through his hands that this is realised for an audience. Robertson will perform the Stravinsky ballets because this is music that matters to him. A good performance can convince an audience that it should matter to them, too.

While the concert hall may not be the raucous space it was in Stravinsky’s day, it doesn’t mean audiences shouldn’t debate and discuss what they experience there. With the selection of works on offer during August, David Robertson and the SSO have set the scene for animated conversation.

– Nicky Gluch

This article appeared in the July edition of Fine Music Magazine – you can subscribe to our monthly magazine and have it posted to your home or business or click the link here to read online.