“It’s scary music, but scary is good,” says Richard Tognetti. “Many people love going to scary films, come to a scary concert.” The Artistic Director of the ACO has joined forces with Synergy Percussion and its Artistic Director Timothy Constable, to create Cinemusica – a concert celebrating the love of film. It will feature a mix of classical works that have been made famous as incidental music, as well as suites of music originally written as film scores. And much of the music in the concert has a darker, scarier edge to it.

The pair spoke to Fine Music magazine, at the ACO’s rehearsal rooms, buried several floors underground at East Circular Quay. They agree that film music has been a very important entry point for people to develop an appreciation of music written in the classical style. “It was a way in for myself,” says Constable.

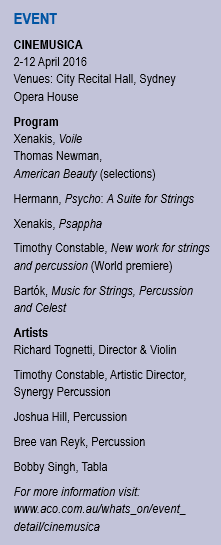

Tognetti adds: “I think for many people this is the portal through which you can travel to access musical sounds that you wouldn’t otherwise listen to, and it also helps to underline the incredible influence that has come from music in the 20th century, that still a lot of people are scared of, yet they’ve experienced all their lives without realising”. But the real ‘scariness’ of Cinemusica, which will be performed around Sydney from 2-6 April, isn’t its origin in the 20th century.

“Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste is scary otherwise Kubrick wouldn’t have used it (in The Shining),” says Tognetti. “And many other people have used it in delightful ways, in a scary context. It was used in Doctor Who, which used to scare the bejesus out of me.”

“Scary can also be extraordinarily beautiful, and in my humble opinion this is one of the most extraordinarily beautiful works written in the 20th century. The most important work written for strings percussion and celeste until…” says Tognetti, pausing to look at Constable. He continues: “…Until this week – it was the only one”.

He’s referring to the fact that Timothy Constable had just put the final touches prior to rehearsals, to his new work for strings and percussion which will make its premiere in Cinemusica. “There’s no celeste in my piece but it could be arranged,” chimes in Constable.

Archetypes of fear

Perhaps the archetypal “scary” music is that which can be found in Alfred Hitchcock’s ground-breaking masterpiece, Psycho, scored by Bernard Hermann.

“Hermann was unfortunately a bit of a failure as a concert composer,” Tognetti explains. “I think it might have been the bane of his existence. He really was desperately trying to be a concert composer – and an accepted one – but didn’t make it.” “As a film composer, I think it’s safe to say that he is standing there in pole position.”

The shower scene with its famous vrink-vrink-vrink soundtrack terrified a generation and re-wrote the rule book on thrillers. Indeed, Bernard Hermann had observed that Hitchcock only finished a film to 60%, and it was up to him to add the rest in the form of the music. How will the film scores ‘work’ in performance without the context of the film and visual references?

“There’s two very strong categories of music on this program, and used for film generally,” Tognetti explains. “One is the monolithic theme that stands alone as a work in its own right, and in the case of the Bartok was a work before it was utilised in film. And then there is the more deliberately spare, stripped-back style of music, which deliberately leaves space for the visuals and that emotional landscape to come in.”

“In the latter case, if the scene’s really iconic, then people are simply going to recall the imagery, and the emotional world that went with that,” said Tognetti.

He continues: “In the case of say the Bartok, bits of it may trigger a similar response, but I think you couldn’t help but be compelled by the fact that it’s such a wonderful concert work, and is very strong in that context”. Tognetti recalls the comment of a young child who said that he enjoyed radio rather than television because he “sees more”.

Strings and percussion

“Percussion often sits at the back of the orchestra because it does that very well,” says Constable. “There are a lot of percussive sounds that articulate time, and punctuate the larger rhythmic slabs in a way that’s very arresting – think of cymbal crashes or base drums, it’s a very significant full stop.” “And in more recent times we may be at the back of the orchestra but we’re making far more timbral and orchestrational contributions. From there I don’t see it as a big stretch to integrate more fully,” he says, referring to the collaboration with the Australian Chamber Orchestra. “With film compositions, it’s a bit of a moot point if you are at the back or the front,” Constable explains. “It’s conceived to be recorded where there is parity between all the instrumental groups, and often that forceful forward moving rhythmic material necessitates getting the percussion in the heart of things. It’s just another instrumental group really”. Just another instrumental group, with one notable exception – the musicians must be masters of a wide variety of instruments. “You all need to do everything,” says Constable. “We all have things we prefer to do, but by and large we get around the core instruments. With percussion we’re really talking hundreds, if not thousands, of instruments.” Tognetti interrupts at this point: “Including the piano. We fight about that one.” Constable continues: “Anything that was a bit unusual – whether it was blowing a whistle or making some sort of strange noise – somehow got chucked into the percussionists vocabulary”.

For the love of film

What are the fundamental changes that have occurred from the era of Bernard Hermann and Psycho, and the 21st century to Thomas Newman’s score for American Beauty, which also features in the upcoming program?

“It was much more to the fore,” says Tognetti, referring to the earlier era of film music. “But also the syntax, or the vernacular, was quite different. It came very much from the stream of outpouring romanticism that you find with Eastern European composers.”

“They’d jumped over the psychic terror of the second Viennese school, and ended up in Hollywood composing not neo-romantic, but romantic music. For the most part cinema was an escape,” says Tognetti, adding that this has continued through the work of John Williams. He says: “Thomas Newman very much comes from minimalism, but also his father’s spirit imbibes his music. He writes terrifically for strings even though it’s paired down”.

“scary can also be extraordinarily beautiful…“

Thomas Newman’s father, Alfred Newman, composed scores for more than 200 films in his career, and is the man responsible for the famous 20th Century Fox fanfare that still can be heard at the beginning of films nearly three-quarters of a century after its introduction, thanks to his time as music director at Fox. “(Alfred Newman) won many Oscars, which are still eluding Thomas,” says Tognetti, before adding, “I would argue robbed – in my mind he’s the greatest film composer alive”.

Thomas Newman has in fact received his 13th nomination this year for his score on Bridge of Spies, but is yet to win the statue. And between Hermann and Thomas Newman, there has also been a dramatic change in the way the film scores are written and recorded.

“You have to remember that when Bernard Hermann was writing music, certainly in the earlier part of his career, it would have been a one-take band. You just had a big orchestra, and synching with the film would have been really complicated. “So, you wrote the score with pen and paper and you handed it out to the musicians. One or two takes later you had the score, which is amazing.” “These days you can spend weeks in a studio altering one note. It’s a very different process and very different sounds have therefore come out of it. Look at the drum music in Bird Man. Listen to the sounds of the instruments in American Beauty,” says Tognetti. Constable adds: “By the time you get to Thomas Newman (and American Beauty) the European tradition has given way to that American influence”. And, we should not forget the “father of all this sound, Aaron Copeland”, according to Tognetti.

“Yes,” says Constable, “in actual fact that American folk music tradition and the Appalachian music which Copeland was not only a fan of, but a great contributor to, is the music of much wider open spaces.” “It’s almost what you don’t put in the score, rather than what you put in the score,” says Tognetti.

One feels like this is a conversation that could go much further and, like the film scores that we come back to either through listening or memory, one we could return to many times with new awareness.

– Simon Moore

This article was a story from the March edition of Fine Music Magazine – you can subscribe to our monthly magazine and have it posted to your home or business or click the link here to read online.